I look up from scrubbing dried yogurt and petrified cereal flakes off my kitchen table and notice it immediately. The persimmon tree that grew oddly off-center in our North Carolina backyard is bare. Yesterday there had been six orange globes dangling from naked branches.

I expect sudden departure from the leaves; every year the tree loses them all at once in an angry rush, a single gust. But the persimmon fruits hang on for weeks—even months longer, heavy with juice and packed into papery skin that glows crimson in a winter sunrise.

Now suddenly they’re all gone. I thud into a stained, damp kitchen chair and sob.

Everything has its season, its cycle. But these persimmons take an entire year to grow, and my children and I watch them the whole time. From the very first pinprick green buds that poke out like magic, to jack-o’-lantern fruits that begin as fisty green patties and change in streaks of orange, then red. We observe, we exclaim, we examine.

“I needed to have a last persimmon. I needed to know it was the last. Without that, I can’t fix it in my mind. I can’t remember it,” writes Jennifer Brookland. Photo courtesy of the author.

“You guys, look!” I’ll call to them each year. “There are leaves on the persimmon tree!” Later, “The persimmons are turning orange!” We go outside to test the firmness. I fret over exposed roots. I squeeze the fruits gently while reprimanding the kids. “Don’t pull them off the tree! They take a whole year and they don’t just grow back.”

Some of them don’t make it, of course. Some we find on the ground, gnawed or nibbled, half-ripe and too late. Deer get them, and birds. My oldest son watched, surprised one fall morning as I leaped up to yell off a murder of crows that had landed peckishly on the top branches. Now anytime a bird lands on the tree he throws open the sliding glass door and screams. To suddenly find our tree absent its cherished fruits is shocking. Unnatural.

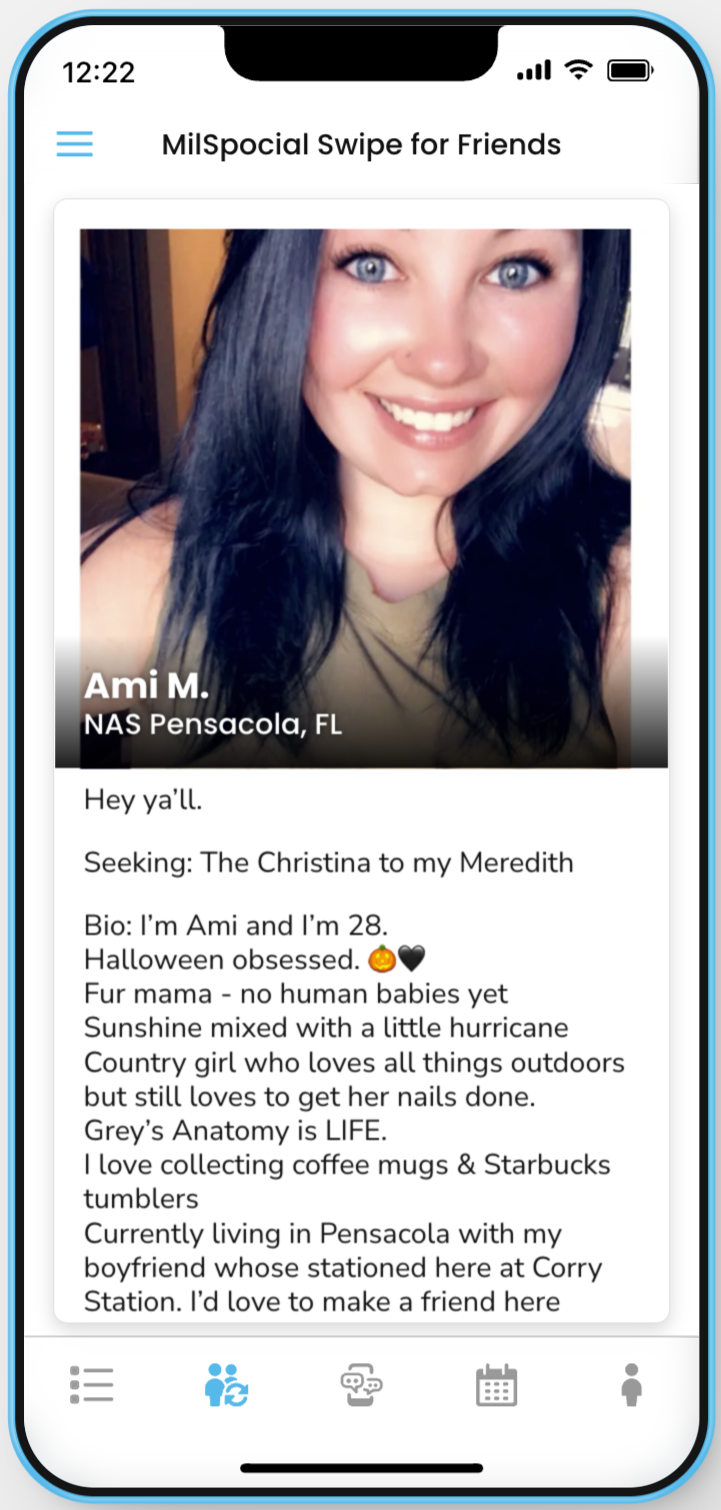

Helping the military community connect personally by creating new ways to socialize.

Life is better with friends.

I have two culprits in mind. My neighbor Airong, who recently moved in and began scrubbing, painting, and scraping with abandon. “Your persimmons are ripe,” she says the second time we meet. She’s holding a spackle brush and her hair is tied up.

“No,” I tell her, “These are the kind you have to let ripen on the branch until they’re practically mush. Otherwise, they’re horrible. The taste makes your mouth feel like all the happiness has been sucked dry.”

“They’re ripe,” she insists. “You pick them.” Her English is staccato, but I wonder if the shortness is just her personality.

A few weeks after that encounter some moms in my neighborhood are sitting around the portable fire pit my friend Sara has set up in her driveway. Hers was the first house I went into when I moved here. I was a tear-stained mess with a three-week-old baby and the lurching fear that I was doing a disservice to this tiny creature by being his incompetent mother. When the card game and gossip were ending, someone helped me clip my nursing top back into place and someone else helped tie my shoes as I held my sleeping infant, and I thanked them profusely, feeling awkward and inept. Seven years later they ask me when the moving trucks are coming, whether we’ve packed yet, and what route we’ll take across the country to a rental home devoid of fruit trees.

My neighbor to the other side, Nusra, mentions that she took a persimmon from my tree and, she admits with a shy shrug of her shoulders, it was delicious.

I smile. “Oh, good!” I say lightly. But I am incredulous. This person has trespassed onto my property and taken one of my precious persimmons. I find it almost impossible to believe and yet she has told me so, with only a hint of embarrassment.

Now, a week or two later as I weep at my kitchen table over their unexpected absence, my angry mind races to blame one of these women. I feel a sense of bereavement that I know, even in the moment, is outsized. But in a few weeks, my family will not own this home anymore. That tree will not be our tree. I will never again taste the breaking sweetness of that orange pulp and watch my children lick the sugary goo from their fingers. I needed to have a last persimmon. I needed to know it was the last. Without that, I can’t fix it in my mind. I can’t remember it.

The Story and Mission behind Military Social Network

As I aimlessly pushed a stroller about the streets for hours, I realized my life as I previously knew it, had somehow escaped me.

I need to say goodbye to this house, but leaving it feels like grief. When I leave this house, I’ll leave behind the physical spaces that allow me to remember. The spot in the kitchen where my son pushed his way to a stand for the very first time, his wobbling hands pressing the top of the wooden step stool where puzzle letters spell his name. He looked over with a smile when I shrieked at his accomplishment—surprised and joyful.

The chair that I nursed him in for what seemed like hours every day. In the night, his fists would reach up to feel my face and then drop slowly, slowly down as he descended into sleep until, finally, the satiny plumpness of his arm rested completely on mine. Out here, on the porch, I watched him push cylindrical blocks down each crack and pretend they were trains as I marveled at his exploding mind, his amazing potential.

“That room with those books and those children, it will disappear one night while I’m doing the dishes and scrubbing that old table. The spray of the running water will drown out the loss. It’s that silent,” writes Jennifer Brookland. Photo courtesy of the author.

Every corner of this space triggers a memory, a feeling. Some are tinged with tears and some still make me laugh out loud, but will I get to keep them? When I leave this place, will my memories stay behind, tucked into its corners, echoing faintly from its bare walls?

Maybe I fear this loss because I’ve forgotten before. I spent four years in the military and remember it in fuzzy flashes. The little I do recall leaves me with a vague sense of awkward incompetence, confusion, and shame. Riding in a bread truck in Djibouti while the Marine I’m across from pulls out his penis just to see what I’ll do. Lying on the ground in tears after my back gives out during hand-to-hand combat training, the weight of my body armor forgotten in the pain, my commanding officer’s head momentarily blocking the sun as he walks past me without a glance. The anxiety in the pit of my stomach as I drive to a prison in Georgia, rehearsing what I’ll say to the airman arrested for child sexual assault to get him to talk to me. His expression when he smugly refuses.

I don’t remember details. I barely remember faces. There are no conversations, no full and funny stories I can trot out at parties, around fire pits more than a decade later. My husband is made of stories from his time in the military. Stories about missions, about near misses. About all-night planning, break-of-dawn workouts, friendships and brotherhood forged in the crucible of combat. For him, like most of the vets I know, his service has grown into part of his identity as rock from different geologic ages melds into a smooth cliff face. He can’t separate his service from who he is.

But I am a forgetter. My memories slide away like trickles of water over stone. If my service didn’t become a part of me, did it matter? If I can’t remember the way my daughter’s laugh sounded when she hid her head underneath the covers, or the way the morning light striped my son’s face when we peeked through the curtains in his bedroom, will motherhood just be another grainy feeling—flat and shrinking? Just a time in my life that happened, and ended?

Enjoy this time! they tell me, those older parents whose children no longer creep into bed with them in the night. My son’s warm hand cups my neck as he falls asleep. I wonder if he’ll pee in my sheets. It goes by so quickly, they tell me. And I agree, nodding with them as I check my watch. Six hours until bedtime.

There are hundreds of thousands of seconds in a day. As I get older—as my children get older—they seem to slide faster, grains of sand in the little blue teeth-brushing timer we always forget to use. How can I hold on to all the drops that formed those sweet pools of my children’s childhoods? Every time I try to cup water in my hands, they reach my lips empty.

“I feel a sense of bereavement that I know, even in the moment, is outsized. But in a few weeks, my family will not own this home anymore. That tree will not be our tree,” writes Jennifer Brookland. Photo courtesy of the author.

I do remember the hours we spend making magnet palaces. The light shining through them casts squares of color onto the carpet, elongating and fading as the sun shifts in the sky. We put on Christmas music in August, marching together like toy soldiers circling the kitchen island. I attempt a pirouette and all three of them copy me, tilting and turning. We run down the driveway in the dark on a December night—forgetting our coats in the rush to see the great conjunction. Jupiter and Saturn will never be this close to Earth again in our lifetimes. I try to grasp the weight of this cosmic opportunity, this unrepeatable occurrence.

I try to take more photos. My middle son splattered in mud, eyes squeezed shut against a swarm of raindrops, grinning after a belly flop through a flooded sandbox. Chocolate ice cream dripping from my daughter’s chin, her hands and hair smeared and sticky. My older son wearing the paper crown he colored on his 100th day of kindergarten, one missing tooth showing a gap as wide as his doubt—even then—that the tooth fairy was real.

I force myself to write things down. The way my son says “ding-bell” instead of doorbell. The time we ran through the rain holding hands and laughing. The first time she said, “I love you” and not just, “I love you too.”

But without something tangible, it’s hard to hold on. I don’t remember the last time I rocked a baby to sleep in my arms, and placed her gently on her back, not daring to exhale. I don’t remember the last time my child smiled and I didn’t see teeth. I didn’t know the next night she would say, “no song.” I didn’t know that sometime in the night a tooth would poke through, unreturnable.

One day I will read them a story before bed for the last time. I will turn out the light and walk out of the door without knowing that I will never be able to open it again. That room with those books and those children, it will disappear one night while I’m doing the dishes and scrubbing that old table. The spray of the running water will drown out the loss. It’s that silent.

Maybe if I forget the details, the feelings I’m left with will be enough: sometimes dry and astringent like an unripe persimmon you just didn’t have the patience to wait for, swaying lonely from a bare winter branch. Sometimes exploding with sweetness, with gratitude for each new season, for each change.

Those branches always bent, they never snapped. Even after the deer came and the birds and squirrels left pokes and scrapes in the hard flesh, the persimmons did return. I was always more protective of that tree than I needed to be.

Author

Jennifer Brookland

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.